In recent years we have seen big, positive changes in public attitudes towards mental illness, suicide and HIV, which have been reflected in, and to some degree shaped by, how these are talked and written about by opinion formers.

Regrettably, there has been no such change in relation to homelessness, which is still associated with a high degree of stigma. This causes much harm to people affected by homelessness and continues to influence the way the public think about homelessness, and thereby shapes political responses.

From a long career in journalism, including working on local and regional newspapers and 20 years at The Times, I know that most reporters and media executives want their coverage to be fair and accurate, however robust it may be.

I also know that some reporters may be expected to write multiple stories in a day, sometimes based on copy from a news agency or to match an article published elsewhere, and on occasions with limited opportunity to engage with primary sources. And all of us, usually unconsciously, may at times use words or a turn of phrase that, on reflection, may have lacked nuance or reinforced stereotypes.

It was with this in mind that we at the Centre for Homelessness Impact commissioned two researchers with expertise in cultural psychology to analyse how words and phrases – and the context in which they are used – can impact on public attitudes towards homelessness. Drawing on this work they have developed a checklist for people writing and speaking about homelessness to help them avoid inadvertently perpetuating harmful assumptions about people experiencing homelessness.

Dr Apurv Chauhan, Principal Lecturer in Social and Cultural Psychology at King’s College London, and his colleague Professor Juliet Foster, Dean of Education at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience at King’s, collected 4,505 social media posts by UK users that referred to homelessness. These were taken from Twitter, before its purchase and takeover by Elon Musk, as a way of looking at how people discuss homelessness in a naturalised, everyday manner. Messages from suspected bots were excluded. To these were added a further 916 sentences featuring phrases commonly used in the homelessness charity sector and in UK newspapers when reporting on homelessness.

The sentences were reviewed by people with personal experience of homelessness, working in pairs, to identify those that they judged to be talking about or representing homelessness in a negative manner. Just under one in five of these – 943 sentences – were rated as negative or pejorative by both members of a pair.

This corpus of writing was analysed by Dr Chauhan and Prof Foster using a method of conceptualising stigma developed by two American social scientists (the Link and Phelan Framework) by looking at ways in which the references to homelessness used labelling, stereotyping, created a sense separation, implied loss of status, or were discriminatory.

Their report finds recurring patterns of references to the appearance of people experiencing homelessness, common implications or accusations of personal shortcomings or bad life choices, and frequent links to substance use and addiction. They also noted descriptions that suggested individuals affected by homelessness were socially undesirable, of lower social standing, behaved abnormally and lacked human qualities.

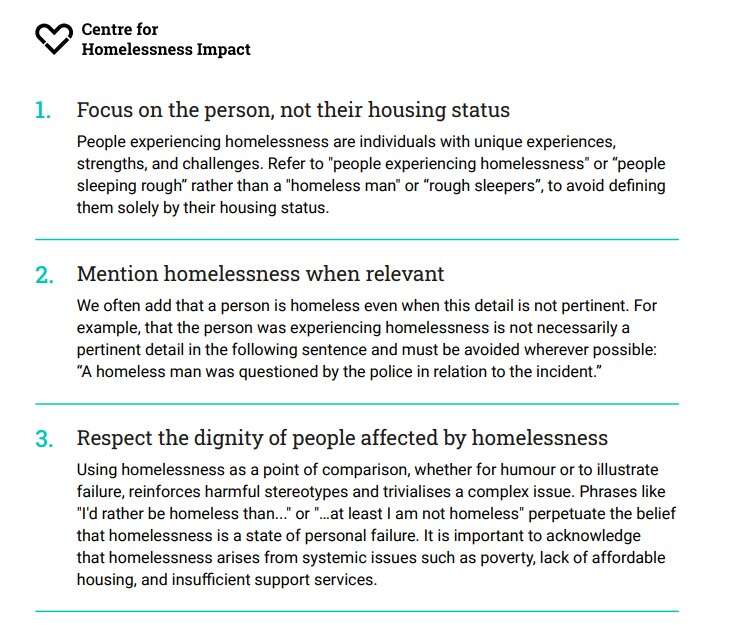

Drawing on this research, their checklist for better language on homelessness seeks to offer practical, evidence-based tips for how to report on or talk about homelessness in ways that avoid reinforcing stigma.

For instance, the checklist suggests using language that does not confuse homelessness only with rough sleeping, thereby overlooking the tens of thousands of families with children living in temporary accommodation because they are at risk of homelessness, or people ‘sofa surfing’ or in other forms of hidden homelessness that are not captured by official data.

It suggests avoiding terms such as “a homeless man” or “a rough sleeper” or “the homeless”, which define people not as individuals but solely by their housing status. And it suggests checking carefully before making any link, and particularly before implying a causal connection, between homelessness and substance abuse. Some people impacted by homelessness have a drug or alcohol problem, but by no means all.

Their checklist is, of course, advisory. It is intended to help anyone reporting or talking about homelessness to do so sympathetically, or at least neutrally. One of its inspirations is the Samaritans’ media guidelines for reporting suicide, which in my experience is widely respected among journalists.

Our hope is that, over time, it will help to shift the narrative around homelessness and shed some of its stigma, just as we have seen when reporting or discussing suicide, mental illness and HIV.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog